This is a fabulous piece of music. I also first heard Karl Denver’s version back in the early 60s. Obviously back in the 30s to the 60s it certainly was the wild west and some of todays publishing houses were built very differently. I know of latin songwriters with now very famous standards selling off literally piles of songs/music to major publishers in NY. It was obviously a very different world then and accepted practice. I found an article that seems to explain the background of this song very well….

Wimoweh.

For the last 50 years, that happy little word has been a universally recognized shorthand for the song known as “The Lion Sleeps Tonight.” From Pete Seeger’s version in 1952 (titled “Wimoweh”) to the Tokens’ No. 1 single in 1961 to its featured role in the hugely popular Disney film and Broadway musical The Lion King, the song has enchanted generations, sold millions of copies and passed into the world’s musical vernacular as a modern folk tune.

But the history of “The Lion Sleeps Tonight” is anything but happy.

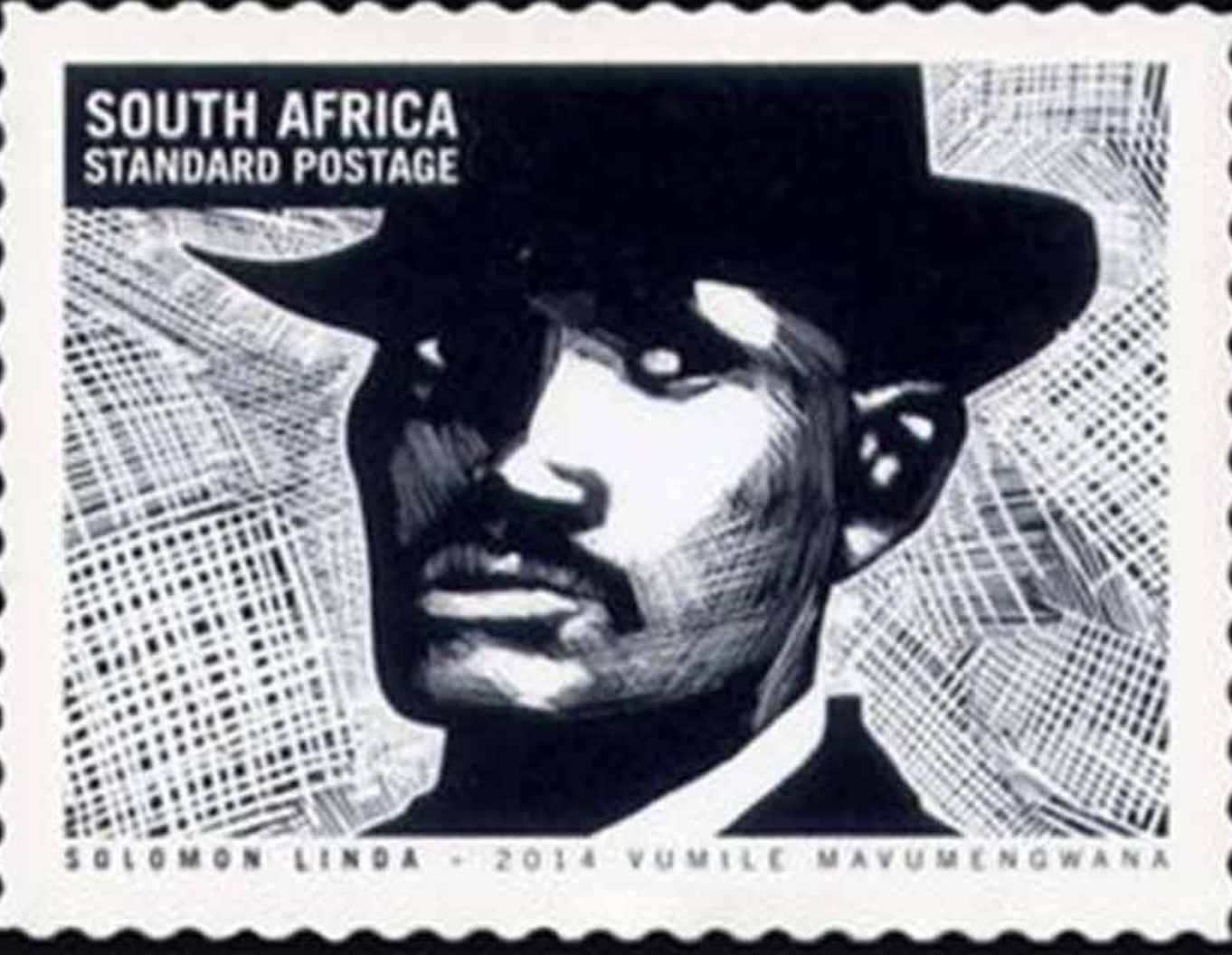

Solomon Linda was born in the Zulu heartland of South Africa in 1909. He never learned to read or write, but he had a knack for songwriting. In his mid-20s, he moved to Johannesburg, where he led an a capella band that charmed audiences in the local beer halls. He sang in a high soprano over four-part harmony chants, a style that would come to define a whole generation of Zulu music. This sound was the basis for many of Linda’s songs, including his most famous, “Mbube.”

In Zulu, “Mbube” (EEM-boo-beh) means “lion.” During his childhood, Linda had worked as a herder protecting cattle in the African hinterlands. The main predator was the lion. The spartan lyrics of his song center on the phrase “mbube zimbe,” or “lion stop.” When Linda and his group, the Original Evening Birds, cut a 78-rpm recording of the song in 1939, it became the first African record to sell over 100,000 copies.

n the ‘40s, the song’s popularity spread through Europe. Though record companies in the U.S. weren’t interested, noted folk music historian Alan Lomax was. If not for Lomax, “Mbube” may have remained an African folk song. But he played it for his friend Pete Seeger. Delighted by the joyous call of what he heard as “Wimoweh,” Seeger worked up a version with his band the Weavers. Their 1952 record, with the Gordon Jenkins Orchestra, was basically them singing the title word with vocal flourishes over four simple chords. A Top 20 hit, the writing credit went to“Paul Campbell,” a pseudonym for the group. There was no mention of Solomon Linda.

Pete Seeger has recently said of the publishing situation, “I didn’t realize what was going on, and I regret it. I have always left money up to other people. I was kind of stupid.”

That same year, Linda had received 10 shillings—roughly 87 cents today—for signing over the copyright of “Mbube” to Gallo Studios, the company that produced his group’s original record. As compensation, they also gave him a job sweeping floors and serving tea in their packing house.

Meanwhile back in the states, the song became a popular staple for nightclub acts. The Weavers’ live version gave it another boost in 1957. Then in 1959, the Kingston Trio had a minor hit with it. Writing credits were listed as Campbell-Linda. In 1961, producers Hugo & Luigi hired Brill Building tunesmith George David Weiss to add lyrics to “Wimoweh” and it became “The Lion Sleeps Tonight,” a No. 1 hit for the Tokens. Within two years, there had been over 150 cover versions worldwide, in languages from Japanese to Finnish. Linda’s name had once again disappeared from the writers’ credits.

“Mbube” was now buried beneath two layers of pop arrangements—and two titles—but it was still Linda’s melody and concept. The royalties that he was supposed to be receiving on “Wimoweh” and “The Lion Sleeps Tonight” (paid by publisher the Richmond Organization) should have made him a rich man. But he got paid only on “Wimoweh,” and for that, less than 50 percent of what he was due.

It must have been much less, because in South Africa, Linda’s eight children survived on porridge and chicken feet (two died from malnutrition). And when Linda himself died in 1962, he had the equivalent of $22 in his bank account. His widow couldn’t even afford a gravestone for him.

The inequity went on for years, with Linda’s survivors never questioning the meager royalty checks they received (from 1991-2000, the years that The Lion King ruled on screen, VHS, DVD and stage, they got approximately $17,000). In 2000, South African journalist Rian Malan wrote an exposé for Rolling Stone, embarrassing several major players in the music publishing world and attracting lawyers to Linda’s family.

In 2002, director Francois Verster furthered the cause with A Lion’s Trail, a documentary tracing the long journey of “Mbube” to “The Lion Sleeps Tonight.”

Justice seemed to be a court case away. But it was no simple matter. Not only had Linda signed over the copyright to his song, but his wife and daughters had twice done the same in the years following. Ownership of “Mbube,” “Wimoweh” and “The Lion Sleeps Tonight” was a tangled mess. When lawyers finally sorted it out in February 2006, Linda’s survivors began receiving the compensation they deserve (the settlement applies to royalties dating back to 1987).

Sadly, there was one final injustice—in 2001, Linda’s daughter Adelaide died of AIDS at age 38, unable to afford a potentially life-saving anti-viral treatment.

When Solomon Linda wrote a song about lions preying on cattle, he could never have imagined the ultimate irony—that he was inviting a much more savage breed of predator into his own life.

—by Bill DeMain

From Performing Songwriter Issue 95